The most fundamental experience of being human is biological. We enter the world in a state of biological dependence, having left an utterly symbiotic existence in the womb. Parents’ first thoughts about a child are consumed with biological issues. Nursing, digestion, sleep, and various discomforts rightly occupy the often sleep-deprived parents of newborns. Conversations among young mothers tend to circle around those issues. Biology is primary. When something is biologically amiss, everything else has a way of being diminished. As years go by, our biological attention sometimes wanes, particularly when things are physically going well. We take our bodies for granted and begin to imagine that the world of thought and social interaction are primary. Of course, aging has a way of bringing things full circle. I warn people these days when they ask, “How are you doing?” I tell them that asking an old man how he is doing is an invitation to an information dump.

This pattern, our movement from the biological to the social and psychological, is also a pattern that can be seen in the history of our species. Civilization did not come into existence at the same time as our biology. Mere survival for hunters and gatherers required some level of cooperation. However, what we think of as civilization (villages and such) only came with the advent of an abundance that placed less immediacy on the primary needs of the body.

This is reflected in the incarnation of Christ. God became man, making Himself accessible in a manner that acknowledged the primacy of our embodied existence. God did not become an idea, a mere expression as a message from a prophet. He became a biological human being. St. John wrote:

That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we looked upon and have touched with our hands, concerning the word of life—the life was made manifest, and we have seen it, and testify to it and proclaim to you the eternal life, which was with the Father and was made manifest to us…(1 John 1:1–2)

or, most famously: “And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us.” (John 1:14)

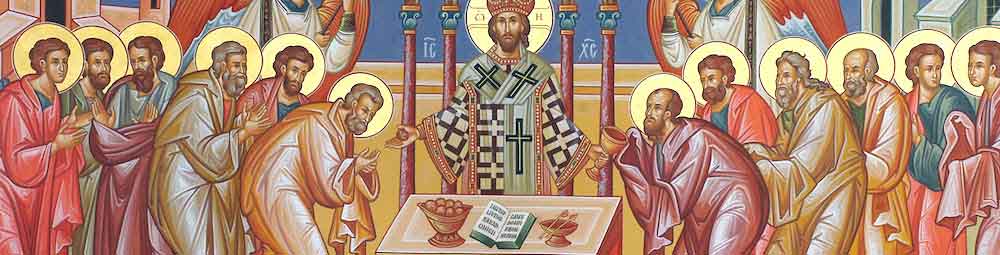

As “civilized” people, however, we seem to have a drive towards an imaginary, disembodied existence. In our contemporary setting of the internet-webbed world, this drive is all the stronger. Jesus as “idea” is all the more tempting. The life of the early Church was, on the contrary, a life of sacrament, a world in which the taste, touch, and feel of Christ and the gospel were primary. It was also a world in which, to an extent far greater than today, the biological aspect of our existence was far more prominent and undeniable. Technology has allowed us to “manage” the necessity of biology in a manner in which it largely becomes an inconvenience in comparison to the unfettered imaginary existence of the mind. We say of the passions that run through our brains, “This is my true self, my freedom, my undeniable truth,” while we suppress our biological reality with baths of chemicals and surgeries, which, like the costumes we assume, seek to hide and obscure the naked truth of our being.

To this, God says, “This is my Body,” pressing the broken, bleeding, biology of His crucified Incarnation into our mouths. “Take, eat…drink this…” Almost immediately we seek to transmute His tasty flesh into an idea, as though He had said, “Take, think….”

That huge segments of the Christian world have negated the reality of His Body and Blood is not surprising. At the same time, the doctrine of the atonement has been transformed into a moral transaction in which the biology of His suffering becomes a problem to be explained (often reduced to a moral tale – “Look what pain your sin caused!”) In such scenarios, sin is reduced to moral failing. But the Scriptures are clear: the biology of sin is primary. “In the day that you eat of it you shall die.” More than anything, sin is mortality. Whatever moral issues we might have spring from the biological death to which we are subject.

And so our embodied Savior says, “Unless you eat my flesh and drink my blood, you have no life in you.” And, “Whosoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood will never die.” The ultimate seal of His promise is found in His resurrection. There, His body is not put away, some temporary thing whose purpose is fulfilled. Instead, that temporal biology becomes the eternal vehicle of Life (bios becomes zoe).

St. Paul, in discussing problems surrounding marriage, adultery, and fornication, ends with an astounding statment: “Glorify God in your body.” (1 Cor. 6:20). The body and its proper sexual action is not a moral problem, but a locus for the glory of God. The old English marriage service, in the Book of Common Prayer, has the groom speaking this phrase:

With this ring I thee wed;

With my body I thee worship;

With all my worldly goods I thee endow.

I can think of no other place in English literature that more completely describes the fullness of marriage in its utter union of husband and wife. It is sacrament.

The atonement is rightly understood as Christ’s direct assault on death itself. It is for this reason that St. Paul describes us as being “baptized into His death.” In His death and descent into Hades, Christ “tramples down death by death.” His triumphant death now becomes our death by water and the Spirit, so that our death is now a Passover and not our destruction.

Many of the abstract theories that surround the atonement, as well as modern pietistic Christianity, are divorced from our bodies. Being “born again” has been divorced from Baptism (whose connection is quite clear in Scripture), and reinterpreted as a quasi-emotional experience, a definition that is no older than the 18th century or so. Baptism itself is often reduced to nothing more than token ritual. In the same manner, the Eucharist, the undisputed center of the Christian life for 1500 years, has equally been reduced and gutted. For some modern Christians, the only doctrine of the Eucharist cherished by the faithful is that it is not the actual Body and Blood of Christ. It becomes a “sacrament” of anti-Catholicism.

St. John makes this simple declaration in his second epistle:

For many deceivers have gone out into the world who do not confess Jesus Christ as coming in the flesh. This is a deceiver and an antichrist.

This, of course, is not the intention of those who have evolved a non-sacramental Christianity. However, the deep anti-embodiment that permeates our culture (and fuels such theology) has set itself on a course towards an antichrist of St. John’s definition. Given the increasing alienation of what it means to be human from our own bodies, Christ’s words, “This is my body,” need to be carefully re-read.

Along with this admonition, we need to return to a consciousness righty grounded in our own embodiment. To live embodied is to acknowledge limits, and to properly respect them. The limits of our bodies should be honored rather than treated as cumbersome obstacles. Our bodies are not given to us as objects to be transcended. Medical experimentation, however noble in its intentions, needs to be reined in with genuine regard and veneration for our limits. An embryo, for example, is a human being, not a scientific tool or toy.

St. John of Damascus offers a profound statement for our consideration:

I do not worship matter; I worship the Creator of matter who became matter for my sake, who willed to take his abode in matter; who worked out my salvation through matter. Never will I cease honoring the matter which wrought my salvation! I honor it, but not as God.

Glory to God who gives us His flesh and blood as the food of immortality. May He grant us grace to glorify Him in our own bodies!

Leave a Reply